Eric Fisher's brilliant

maps of ethnic group distributions in US cities, inspired by Bill Rankin's original

map of Chicago, have rightly attracted lots of praise (see

here and

here). Eric's map of New York is shown below. Using 2000 Census data on the resident population, each dot represents 25 people with the different races colour-coded - White is pink; Black is blue; Hispanic is orange, and Asian is green.

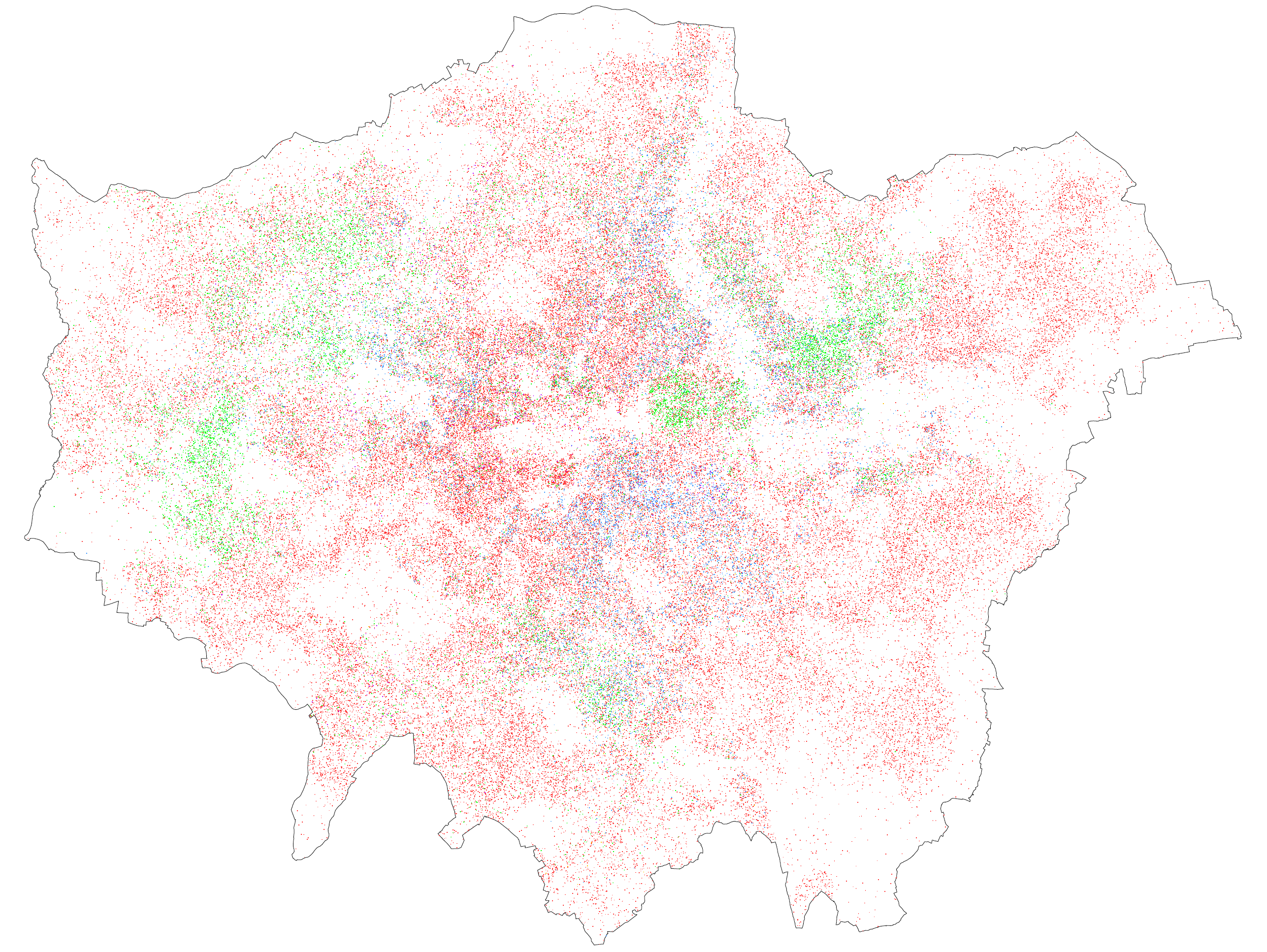

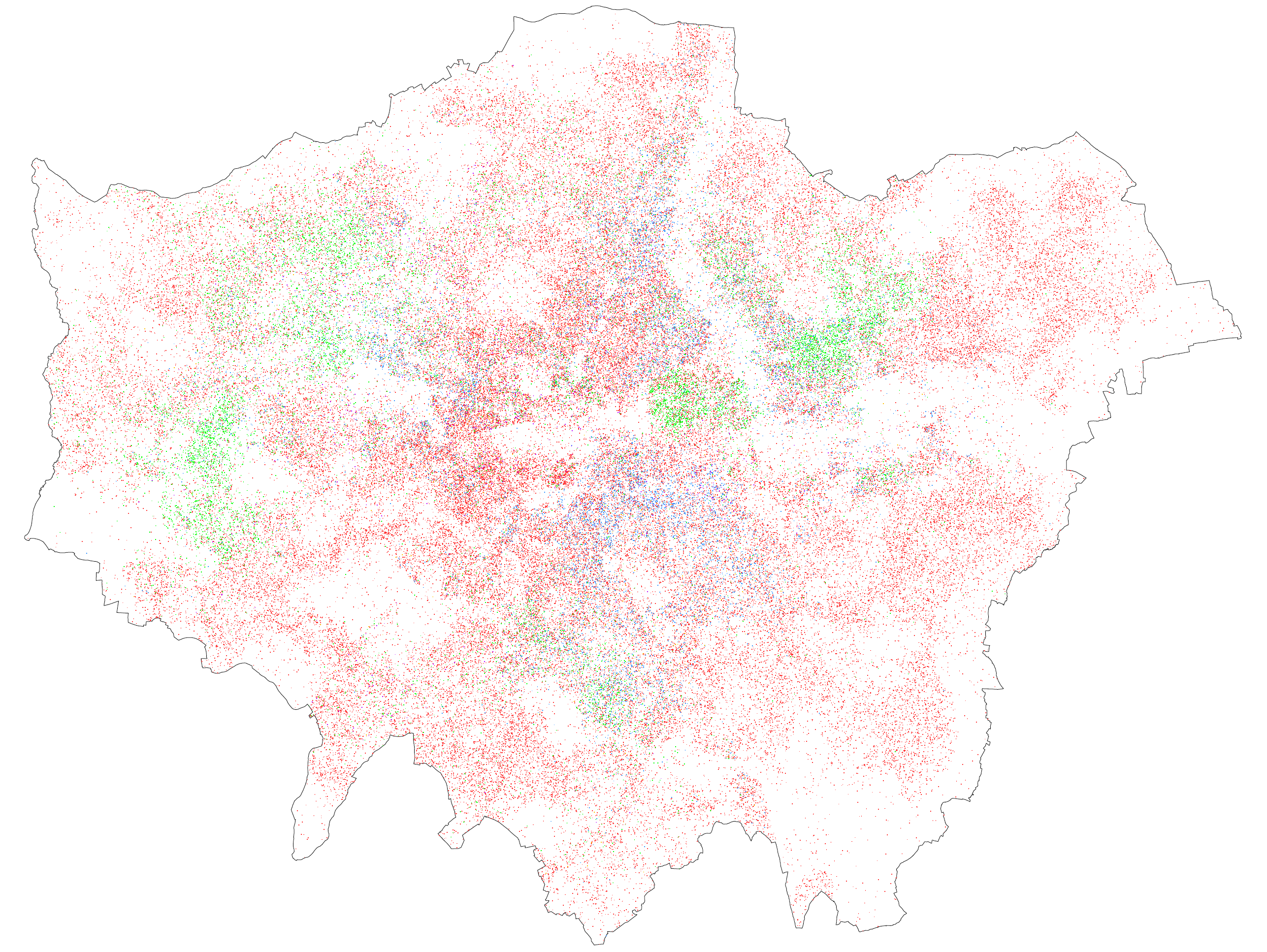

Having chatted with Eric over email about doing a similar map for London, I have produced a first stab at this below (click for a larger version).

The colours aren't quite as vivid when viewed at this scale, but I'd encourage you to click on it to view at full size. I think part of the reason it's less vivid is that I use one dot for every 50 people rather than every 25, in order to avoid what I thought was too much clumping. But it might also be that there is less segregation in the first place.

It should be noted that the underlying data is a bit different. I use 2001 Census data at the Lower Super Output Area level, which is a larger geographic level than what Eric uses, so there is a bit more random scattering than in his maps. The problem, without going into too much detail, is that in the UK Census data at very small area is often slightly tweaked to remove even the slightest chance of identifying individual households, so the real number of (for example) Asian people in a neighbourhood might be slightly different from the number in the data. This problem is worse for the smallest geographic level (Output Areas) which is why I used LSOAs.

The ethnic make-up of London is also rather different from the typical US city. I used the following colour coding (the percentages indicate the share of London's population in 2001):

White - red dots - 71%

Black - blue dots - 11%

Asian - green dots - 12%

Mixed - purple dots - 3%

Chinese and other ethnic groups - orange dots - 3%

I'd be interested in anybody's comments about the map, in terms of both format and whether any conclusions can be drawn from it. At first glance it looks like London is less 'segregated' by ethnicity/race than most US cities, which would correspond with my preconceptions. Let me know what you think!